The statutory regime underpinning the provision of youth services in England is set out in section 507B of the Education Act 1996 (as amended). The provision places a duty on local authorities, “so far as is reasonably practicable,” to secure access for “qualifying young people” in their area for “sufficient educational leisure-time activities which are for the improvement of their well-being, and sufficient facilities for such activities; and sufficient recreational leisure-time activities which are for the improvement of their well-being, and sufficient facilities for such activities”.

“Qualifying young people” means those aged 13 to 19 years inclusive, and also those aged 20 to 25 years inclusive who have a prescribed learning difficulty or disability.

The term “sufficient” in relation to activities or facilities, means “sufficient having regard to quantity”.

Local authorities also have a duty to:

Government strategy: Positive for Youth (2011)

On 19 December 2011, the then Coalition Government published Positive for Youth, a cross-departmental strategy document for young people aged 13-19.¹ It “set out a vision for how central and local government can work more effectively with communities, voluntary and community sector providers, and business to help all young people succeed”.²

This was followed by revised statutory guidance for local authorities on services and activities to improve young people’s well-being, published by the Department of Education in June 2012. While it sets out the principles of locally delivered youth services, it does not prescribe any activities that must be offered.

Box 1: Recent announcement of review of the statutory guidance

On 10 July 2019, the Government announced that it had launched a review of the guidance for local authorities which sets out how they should secure activities and services for young people. As part of the review process, “a public call for evidence will be open for 8 weeks over the Summer, from late July to September”.³

The UK Government established a number of funds to support its new strategy: more detail can be read in section 1.5.

A progress report on the Positive for Youth commitments was published by the Coalition Government in July 2013.⁴ It included examples of successful projects and the involvement of young people in decision making. There is some data suggesting that, on some metrics, young people are living safer lives, contributing more to society and happier.

Civil Society Strategy (2018)

In August 2018, the Conservative Government published Civil Society Strategy: Building a Future that Works for Everyone, which included 15 “missions” for the future. Mission three concerned “opportunities for young people”.

Within this strategy, the Government pledged to review the 2012 statutory guidance that describes local authorities’ duties when it comes to youth services (see box 1 above), adding that it “expect[s] that the review will provide greater clarity of government’s expectations, including the value added by good youth work”.⁵

The Government also said that it planned to support

a £1 million evaluation of over 90 projects across the UK, engaging hundreds of thousands of young people, through the Youth Investment Fund. As a result of this, by the end of 2020 we aim to have a shared impact measurement framework for open access youth provision that uses data to improve services, measure outcomes, and predict likely impact. This will be supplemented by a solid evidence base of what works in open-access youth services.⁶

The Government also said that it expected to:

Following the announcement in January 2018 that £90 million from dormant bank accounts would be “spent to help young people facing barriers to work”, the Civil Society Strategy proposes using this funding alongside the Big Lottery Fund to create a new independent organisation that will “harness the experience of grassroots youth workers, businesses, and other local services to build a strong partnership of support around each young person”.⁷

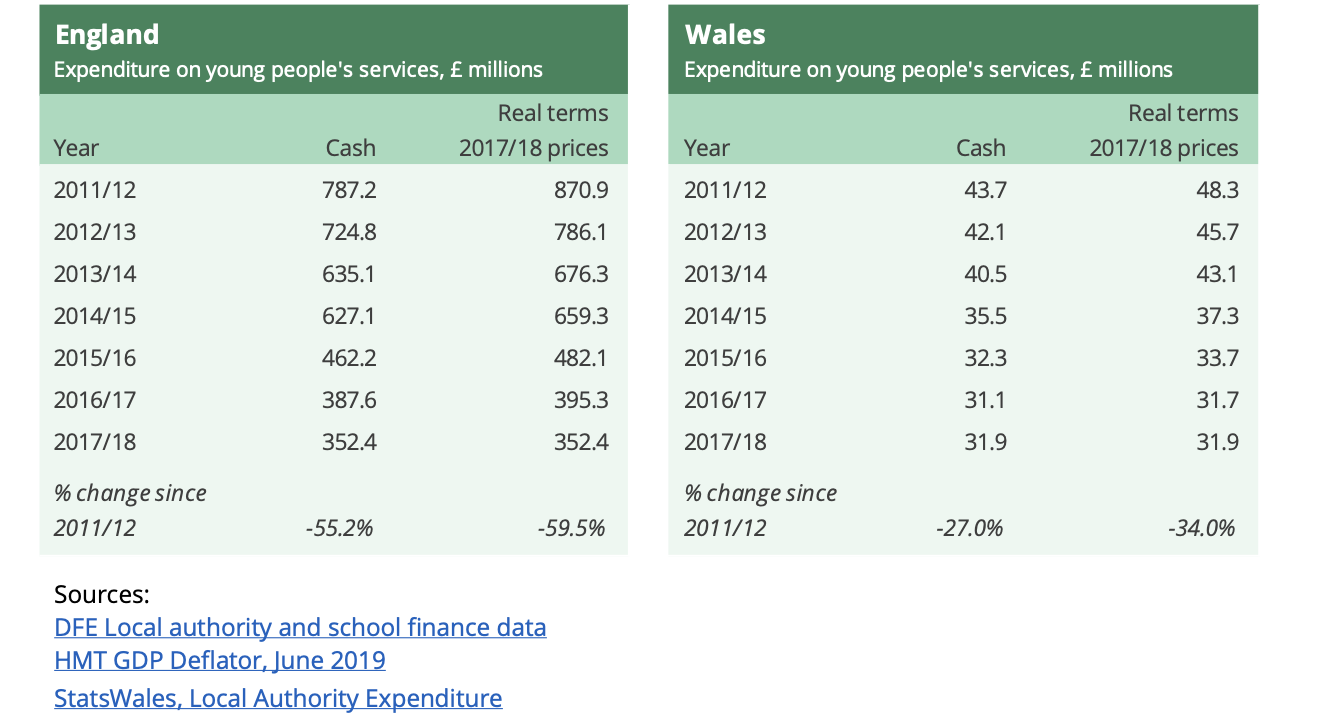

Funding for youth services

Youth services budgets are set by local government and are financed from overall local government revenue funding. Since these budgets are not-ring fenced, there are no direct central government ‘cuts’ to budget allocations. However, information is available on changes in expenditure on services for young people since 2011/12, and this is shown in the tables below for England and Wales respectively.

England trends: Between 2011/12 and 2017/18, expenditure on young people’s services fell by 55.2% in cash terms and by 59.5% when taking into account inflation (‘real terms’).

Wales trends: Between 2011/12 and 2017/18, expenditure on young people’s services fell by 27.0% in cash terms and by 34.0% in real terms.

Due to changes in the financial classification of local authority expenditure pre-2011/12, earlier data is not comparable with current expenditure data. Any comparisons made with pre-2011/12 figures would overestimate the level of decline in expenditure.

In Scotland, the EU Commission’s 2014 report found that, as well as “fairly limited” funds being available nationally, overall grant availability for the voluntary community sector had decreased “significantly.²⁷

¹ Department for Education, Positive for Youth. A new approach to cross-government policy for young people aged 13 to 19, December 2011

² As above, Ministerial Forward

³ GOV.UK, Review launched into statutory guidance for Local Authorities on providing youth services, news story, 10 July 2019

⁴ HM Government, Positive for Youth, Progress since December 2011, July 2013

⁵ HM Government, Civil Society Strategy: Building a Future that Works for Everyone, August 2018, p42

⁶ HM Government, Civil Society Strategy: Building a Future that Works for Everyone, August 2018, p42

⁷ HM Government, Civil Society Strategy: Building a Future that Works for Everyone, August 2018, pp42-45

²⁷ European Commission, Working with young people: the value of youth work in the European Union: Country report United Kingdom, 2014, p.56