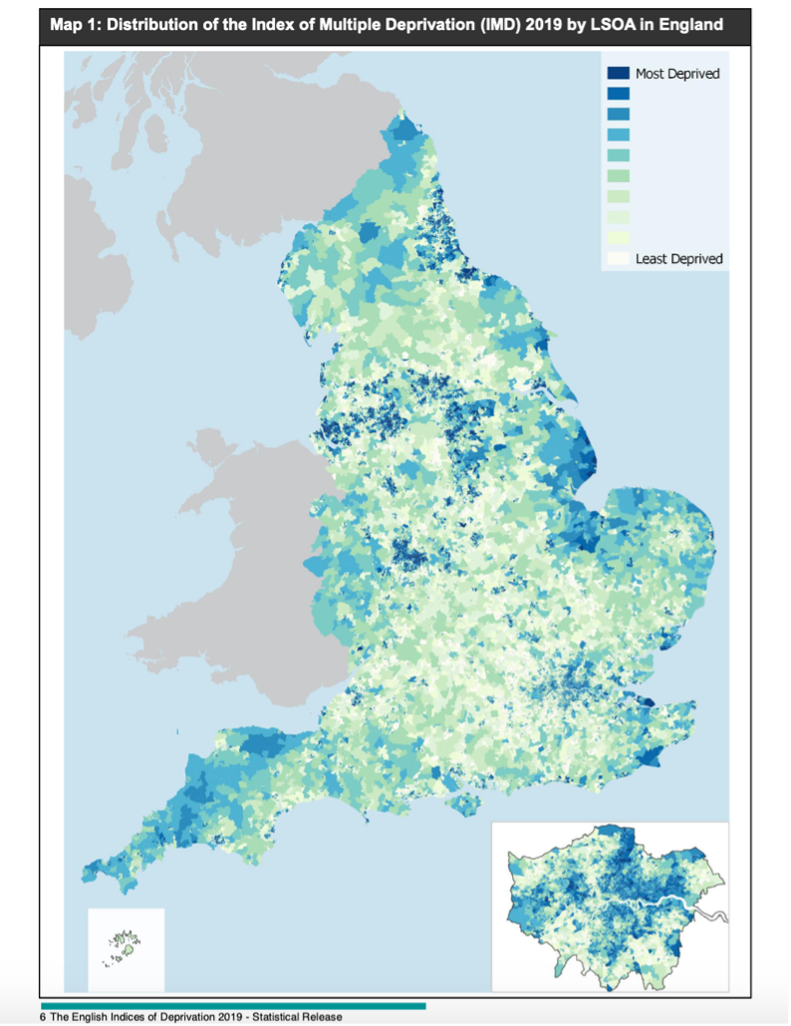

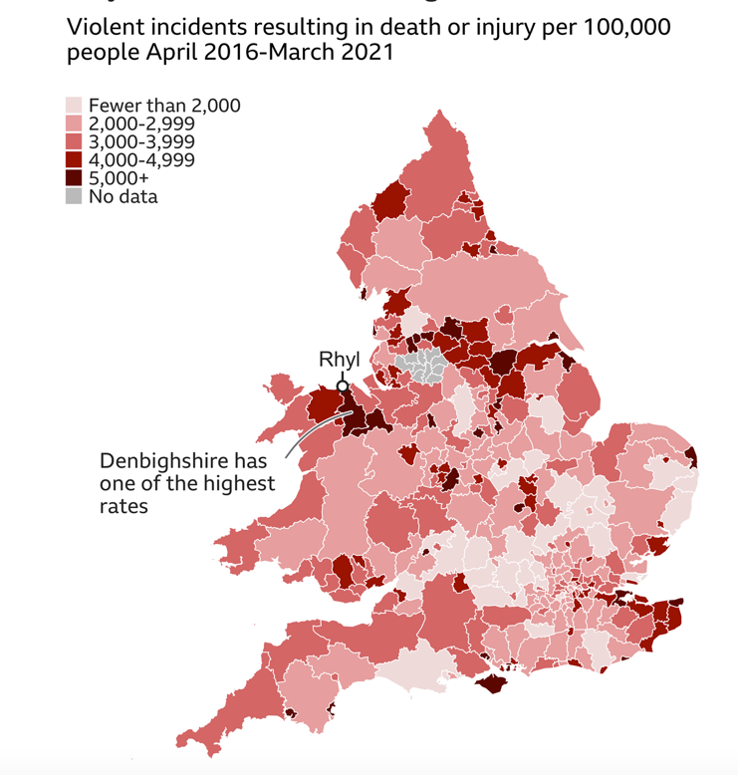

Whenever ‘knife crime’ is mentioned, certain assumptions are likely to be made. It will be assumed that we are talking about a type of crime that is distinctly youthful, that this is a problem located in the inner-city (particularly London), and it will likely be insinuated that this is a problem characterised by youth culture disproportionately represented by Black or Asian young people. But ‘knife crime’ data tells a different story. The majority of knife possession offences recorded and those admitted to hospital for assault by sharp instrument are adults (82% and 83% respectively¹). The highest rates of offence involving a sharp instrument in 2020/2021 were in the West Midlands, with the highest proportional increase in Surrey². And once economic factors are accounted for (Black and minoritized ethnicities are twice as likely to live deprived areas of the UK where individuals are more likely to experience violent crime³) there is no correlation between ethnicity and knife offending.

However, child-on-child homicide with knives is a devastating reality and each young life cut short is a tragedy that sends shockwaves of trauma and harm through communities that are impacted. For all the talk of ‘tackling knife crime’ we’ve seen very little change in rates of violence and homicide between children. So, what is the problem with calling this ‘knife crime’ if it draws much needed attention to the problem? My experience and research in knife crime prevention since 2008, suggest there are several problems with how the label ‘knife crime’ frames violence between young people.

Firstly, talking about ‘knife crime’ rather than violence has led to knife-oriented approaches that obscures the underlying causes. The introduction of the ‘knife enabled’ police crime code in 2001 was an instrumental shift in the way offences with knives are recorded. This new ‘tick box’ in police crime recording systems became the statistical foundation for the crime category ‘knife crime’ that emerges in the early 2000s and begins a process of understanding youth violence through the weapon used for the first time in England and Wales. Along with blades, the definition of ‘knife enabled’ by the Home Office includes all sharp instruments such as screw drivers, broken bottles or glass and the data generated often makes no distinction between incidences of domestic violence, bar brawls, theft, sexual assault, or the age of the offender.

By grouping together violence in different contexts, with varying underlying motivations and causes, ‘knife crime’ presents a weapon focussed conceptualisation of conflict that makes the knife the problem, rather than the violence itself. Since 2008, policy and criminal justice practice have become increasingly knife-oriented and through this the cause and effect have been flipped; we target a ‘knife culture’ in the belief that it causes violence, rather than understanding the violent contexts that made a ‘knife culture’ inevitable. Those working on the ground with young people have consistently recognised the underlying sociological shifts that have intensified violence between young people over past decades⁴, but these crucial understandings are obscured by a societal fixation with the lurid knives and blades that make ‘knife crime’ such a persistent label.

(Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. ‘The English Indices of Deprivation 2019’ (2019) available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/

(adapted from S. Swann & W. Stephenson ‘Levelling up: The seaside town fighting violence and frustration’ BBC News (3rd August 2021) Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-58029524)

Secondly, the overtly racist discourse that frames ‘knife crime’ as culturally attached to Black or Asian children is difficult to separate from the label. I was once facilitating a knife crime prevention project that arranged for young people who had a first-time knife offence to meet with local police officers and ask them any questions they had. One Black teenager asked the officers “why do you always stop and search Black boys?”. A white officer gestured to the group of predominantly Black and minority ethnic young people in the room and replied in a matter-of-fact tone, “well, you only have to look at the people in this room to know that knife crime is a Black issue”. In fact, the representation within the room was proportional to that of school age children in that London borough – but the institutional message was clear.

This interaction during a knife crime project exemplifies the overt and ‘common-sense’ racialisation of ‘knife crime’ in official discourse and prevention practice. It is hardly surprising that such understandings have become normalised, considering that then Prime Minister, Tony Blair, stated in 2007 that ‘In respect of knife and gun gangs… we won’t stop this by pretending it isn’t young black kids doing it’⁵. With more violent overtones, in 2018 the BBC broadcast a Question Time audience member calling knife perpetrators ‘a particular breed of human who… should be dealt with like the cancer they are and exterminated’⁶. The label is also used selectively in the press, with analysis of ‘knife crime’ reports during the year of 2017 finding that in all national press other than The Guardian, the label ‘knife crime’ was only used to describe incidents when the victim was a Black teen or child located in a city⁷. Communication on Twitter consistently demonstrates the vitriolic racism contained in the label ‘knife crime’ – you need only look as far as the reply comments on any image of a knife recovered and shared by police Twitter accounts for evidence of this!

The combined impact of a restrictive knife focus and the racialised notion of a ‘knife culture’ makes the label ‘knife crime’ particularly problematic. However, for many individuals and organisations committed to reducing violence between young people the label provides the only media and public attention that will make the tragedy of child-on-child homicides a policy priority. Working within this dilemma is unavoidable and we will continue to navigate the label and its assumptions in violence reduction work for the foreseeable future. What we can do, however, is be aware of the pitfalls of ‘knife crime’. We can consciously move the conversation beyond the knife and youth culture at every opportunity, and instead draw attention to the brutalising living conditions that have normalised violence in the everyday lives of many young people. We must reject racist discourse that blames culture instead of economic inequality and insist that all children and their families are able to live healthy, happy, and safe lives, within well-resourced communities.

References:

¹ Grahame Allen & Megan Harding, ‘Knife Crime in England and Wales’ House of Commons Library (September 2021). Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/

² Ibid.

³ Gov.uk. ‘People Living in Deprived Neighbourhoods’, found in ‘Uk Population by Ethnicity, Ethnicity Facts and Figures’. (16th March 2018)

⁴ E. Williams & P. Squires. ‘Rethinking Knife Crime; Policing, Violence and Moral Panic?’ Palgrave MacMillan (2021)

⁵UKPOL. Tony Blair—2007 Callaghan Memorial Speech. UKPOL (2007). Available at: http://www.ukpol.co.uk/tony-blair-2007-callaghan-memorial-speech/.

⁶ Evans, A. ‘Question Time audience gasps as man calls perpetrators of knife crime a ‘cancer’ who should be ‘exterminated’ INews (2018) Available at: https://inews.co.uk/news/uk/question-time-knife-crime-cancer-audience-video-220175

⁷ G. Younge. ‘The radical lessons of a year reporting on knife crime’. The Guardian. (21st June 2018). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/membership/