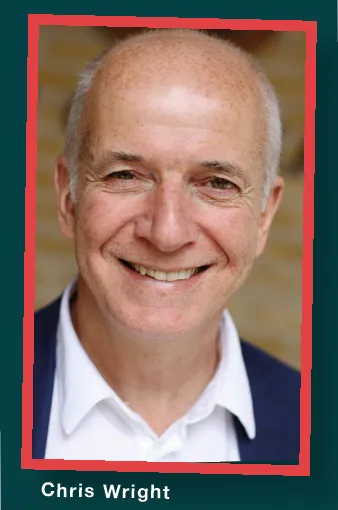

Chris was formerly a senior leader and practitioner in the social justice environment and now works as an adviser, a non-executive director, trustee, and mentor.

I am getting old (er). In 2022 I stepped down as the Chief Executive of the Social Business Catch22 and embarked on a so-called portfolio career working in non-executive director roles in organisations with adjacent interests to Catch22 and indeed my earlier career. Much of that earlier career I spent in both the criminal justice system and children’s social care as well as a stint working in policy at the then relatively newly established Youth Justice Board. One of my observations over this 40-year journey is that if you’re young today its tougher than in my day and the approach to those who seemingly transgress is now more punitive than when I started out on my career.

The common theme throughout this lengthy 40-year journey has been “initiatives”, novel approaches to addressing entrenched problems and “wicked issues”. Of course, public policy is both dynamic and iterative as new governments come and go and new thinking emerges, the evidence strengthens, or particular voices come to the fore or access is gained, and influence achieved resulting in the latest “solution” to the stubborn and seemingly forever resilient policy challenge. And, again I’ve reached a further conclusion, things that work tend to do so despite the system.

So, I come to write this piece thinking what I can add to the debate about knife crime and how we can reduce its prevalence and fundamentally save lives, both victims and perpetrators. I write this the day after the heinous knife attack in Hainault which resulted in the death of a 14-year-old boy and serious injuries to those who came to help or simply were in the wrong place in what appears to have been a random and deluded act.

In January, the Ben Kinsella Trust highlighted that knife crime had “surged” by 5% in 2023 with 48,716 incidents reported by the police. The Metropolitan Police recorded a 22% increase with 13,957 incidents reported.

In 2002 I was working at the Youth Justice Board when the then Home Secretary, David Blunkett, launched his street crime initiative, an earlier effort to address, manage and reduce street crime in all its forms. Indeed, the Youth Justice Board itself emerged out of the Audit Commission’s seminal report on “Misspent Youth” which influenced the emergence of Youth Offending Teams following the implementation of the 1998 Crime and Disorder Act – the concept of the Youth Offending Team was seen as a radical solution to join-up local agencies to work in consort to both prevent and reduce youth crime. And, of course throughout the 20th century criminologists and policy makers have constantly presented original approaches. I was also reminded last week that it is 10 years since Catch22’s Dawes Unit published its highly acclaimed research, focusing on the impact of gangs and violence in prisons.

I appreciate that I might be accused of conflating a number of issues – I started off mentioning knife crime, I’ve moved on to youth offending and gangs and prisons but there is a common thread. Of course, knife crime isn’t limited to young people and nor is gang involvement, but the common thread is that it involves people, people whose lives are debilitated by crime and lack of hope.

But, why does the problem persist? Indeed, it could be argued that the situation in many parts of the country is worsening. From my current perspective at the back end of a 40-year career it certainly feels that growing up today is tough. For much of my generation we grew up within a more certain environment – you went to school, you left school, you got a job or went into higher education, you got on the property market, you retired and received a pension.

Of course, it was not necessarily a linear journey, and for many life was difficult. There were significant inequalities and injustices, indeed many structural determinants of how your life progressed. So, I don’t want to present some revisionist nostalgic picture of the past, but contemporary life for a lot of people is increasingly difficult.

Growing up my generation were not subject to the pernicious influence of social media, nor the increasingly difficult challenge of securing tenure, or repaying student debt or achieving security of quality employment. Additionally, the geo-political environment is again worsening with much of the gains achieved following the second world war and the later fall of the iron curtain being increasingly destabilised.

I am in danger of going off at a tangent. Essentially, I think that growing up today for many young people is full of jeopardy, including being subject to increasing levels of violence and fear. Policy initiatives come and go from situational measures (why are we still waiting for Zombie knifes to be banned?) to preventative programmes, albeit the austerity era has wiped out too much of the infrastructure required to do this well – despite all the evidence of prevention being better than cure. What a hackneyed sound bite that has become. Enforcement has assumed a more prominent place in the lexicon of interventions resulting in a prison population double that of only 30 something years ago – yet recidivism remains at very high levels and the prisoner experience is a blight on our politicians and policy makers, indeed on us all– as Winston Churchill reportedly said “show me your prisons and I shall say in which society you live”. It is probably fair to say that over the last 10 years we have become increasingly punitive in our policy responses to issues such as violence and knife crime.

So, is this a counsel of despair or do I think there are workable, sustainable solutions? I have now reached a point where I think that the answers and approaches, we need to adopt will be achieved in spite of the system. And I am hopeful that the conditions for change are present albeit in need of some further nurturing.

The reason you might be reading this piece is because a few years ago I met Bruce Houlder – a man who has vast experience of our criminal justice system. He wanted to do something about knife crime in London. He had seen the impact of it through his work in the criminal courts of London. I think it is fair to say that he found trying to make sense of the plethora of initiative across London somewhat bewildering and so went about trying to create a platform of sorts to bring the respective interests and parties together to forge common ground. And, for me this is a significant part of the answer. Over the last 20 years I have become interested in the notion of collective impact, a methodology or approach to addressing societal problems that emerged in the United States. The principles of collective impact are:

• It starts with a common agenda.

• It establishes shared measurement.

• It fosters mutually reinforcing activities.

• It encourages continuous communications.

• It has a strong backbone.

*For more information check out www.collectiveimpactforum.org

This is not some simple gimmicky type of solution. It requires hard work, it requires focus, and it requires us all to park our egos in support of a common good. It requires people who are driven to find solutions to find a way of working together, to stop competing for space and resources but to collaborate, to curate and collate resources in a common interest. And it can work. There are numerous examples of collective impact programmes and projects delivering sustainable results that can be found on the above website. I’m personally involved in a collective impact programme delivered through the West London Zone where I’m a trustee www.westlondonzone.org.

This is not a simple panacea, it requires humble leadership, it requires the ceding of power, it requires orthodox delivery structures to be brave, it requires funders to fund what the evidence tells us works. It requires us to stop doing things we have always done or thinking that the next proprietorial policy initiative will be the answer.

Chris Wright

Freelance. Former Social Justice Leader, Formerly a senior leader and practitioner in the social justice environment and now works as an adviser, a non-executive director, trustee, and mentor.