Thirty young people tragically lost their lives to knife-crime in London in 2021, the highest number of deaths in the capital since knife-related records began in 2003. Having been a police officer with the Metropolitan Police for over twenty years, I have been exposed to the violence and trauma that haunts our capital and devastates the lives of many. In the last few years, I was proud to undertake the role as an engagement officer with an East London Gangs Unit that deepened my understanding of the anguish parents, carers and families endure after losing a child to violence.

My interaction with parents and carers revealed they feel unheard, stigmatised and undervalued by the services designed to safeguard them. As such, my work focused on empowering them and creating a platform for their voices to be heard.

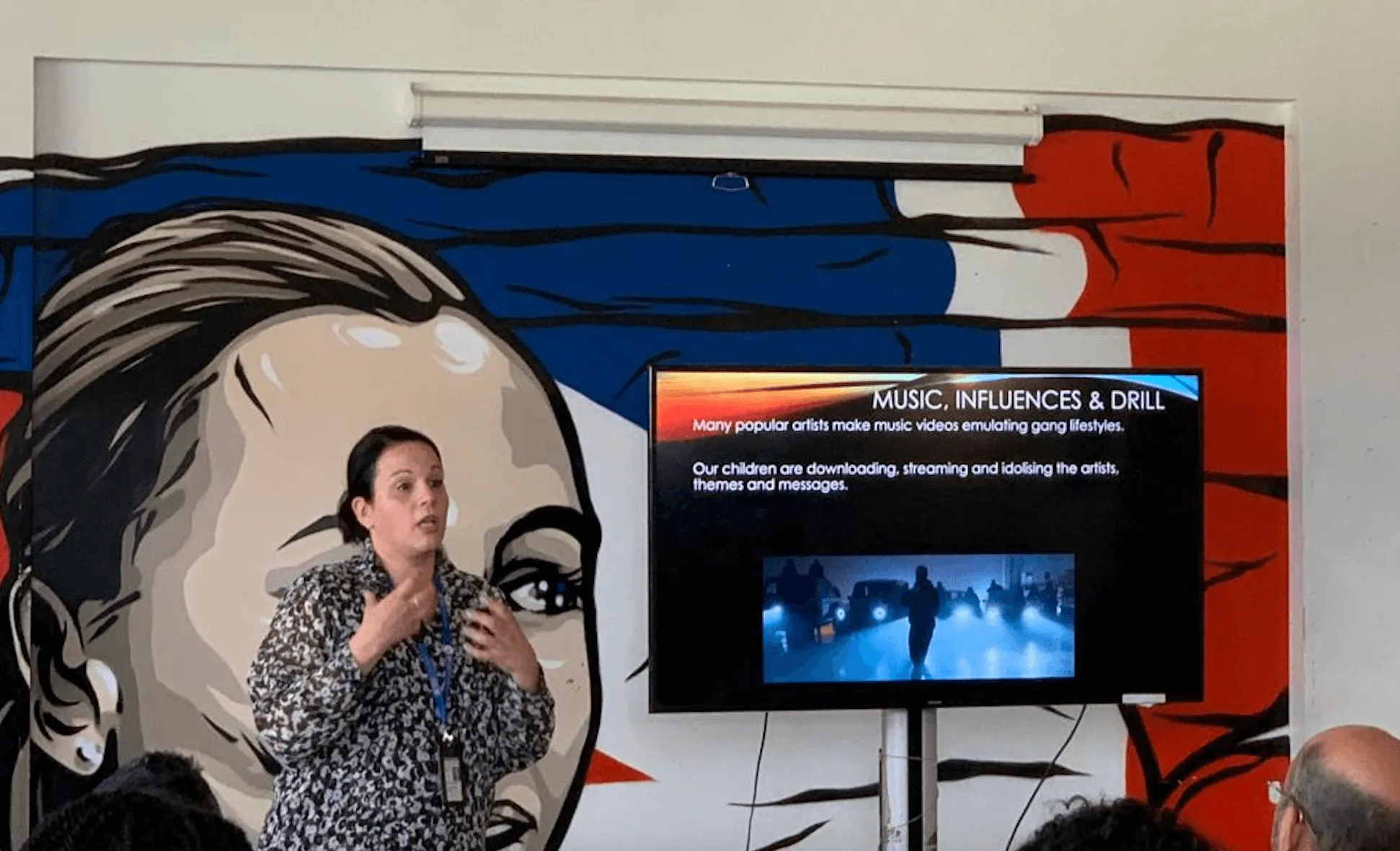

Having identified this gap, I piloted a project that was recognised within a Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme paper on ‘Exploitation, county lines, threats and weapons’ (2020) as promising practice. This project took a universal approach to parent and carer inclusion and education on the subjects that matter to them the most, to ensure they were provided with an understanding of the risks to their children, the factors that may lead to enhanced vulnerabilities, and provided tools and signposting to mitigate these vulnerabilities.

Much of my work has led me to have interactions with mothers who have tragically lost their children and grandchildren to knife-crime. Hearing their painful experiences and the messages of isolation they convey has compelled me to advocate for seldom- heard parents and carers, to help give them a voice, and a seat at the table. It is also my personal experiences as a mother of a teenage boy that leads me to be outraged as a parent, that I could be discounted from the discussions that could protect my own child from such violence.

The pandemic brought new challenges and so the programme was developed into an interactive online format run over three weeks in two- hour sessions, that enabled parents and carers to attend anonymously and be as involved as they felt comfortable with.

Within this safe space we explored difficult subjects sensitively, such as drugs, knives, abuse, neuroscience and trauma. This course was not just about discussing the signs that our children may be getting exploited into that world, but also the vulnerabilities that may make this more likely and how we can develop resilience as parents and as a community. It brought us together as parents, stripped away the stigma attached to the subjects and offered signposting to sustainable support services. The parents and carers were important influences in the course content, with anonymous surveys enabling them to provide input and feedback that in turn enabled me to create a programme that the attendees wanted, their voices included to ensure this was an authentic participatory experience. Between October 2020 and October 2021, over 1200 parents and carers joined, providing testimonies such as,

‘Very different to Gang training I have done before.. this was far more in depth and delivered in a style which kept me interested’

‘Every parent or carer sgould take this course.. Parents should get together with the police we can definitely change the community and make our children feel special and safe’

‘Great, great course. Very informative. Well delivered.. and I was privileged to have attended. Should be made available all over London as I feel so many other families can benefit from it’

‘Really excellent training. Very helpful to understand how everything is linked. The video clips and Anoushka’s examples as a parent herself really help you understand and recognise it’s something that is part of all our experiences. Thank you!’

‘Really valuable training – very well presented. All parents should do this!’

Whilst running this programme and face to face workshops, I also undertook an undergraduate degree and used this opportunity to explore the role that parents and carers have in tackling knife-crime. It is widely accepted that strong attachments with parents and carers are a protective factor in preventing violence and harm in young people’s lives, yet my research identified a significant gap in the existing literature on knife-crime in reference to parent and carer inclusion. This gap in literature is related to both public policy and academic discourse.

The exclusion of parent’s and carer’s voices in the academic landscape of knife- crime is evident and it is imperative to consider why this shortfall exists. It is also clear that on the occasions whereby parents and carers are included in policy, their role is tokenistic. My research identified that there are no collaborative and meaningful frameworks written into policy that include parents and carers in a participatory and sustainable manner. Instead, work appears to be done to the parents. Parents and carers hold a wealth of information and experience, and as such should be included in research and policy responses to knife-crime to better inform the responses and outcomes.

It is through this work which has led me to consider why the voices of parents and carers are excluded from knife-crime and violence strategies. Policy makers must focus on these significantly neglected community members in this phenomenon and summons transformation in how parents and carers are viewed and are involved in its’ solution. We must look at new ways in which to tackle a challenging societal issue by engaging and empowering a distinct community – parents and carers - to understand the vital role they play in preventing knife crime.

‘It takes a village to raise a child’ is a commonly known proverb demonstrating the benefits of community, yet parents and carers are being excluded from the process by the very policies that are designed to safeguard their children. Parents and carers are a valuable and significant factor in tackling knife-crime therefore action is required now to include them in its solution.

Anoushka Dunic, Police officer, Metropolitan Police