In 2005, Glasgow was ruled by I its street gangs. Around 170 such gangs existed across the city, collectively employing nearly 3,500 members aged between 11 and 23.1 The violence was so dire that someone fell victim to a serious facial injury once every six hours. The Scottish Violence Reduction Unit (SVRU), born out of Strathclyde, was a direct response to these surging rates of violent crime.

In October 2008, two police officers Karyn McCluskey and John Carnochan from the violence reduction unit devised a scheme that would go on to turn Glasgow’s fate around. They invited the gang members to a community meeting, a ‘call-in,’ alongside those that had directly been affected by the violence. This included former gang members, mothers of victims, and a local surgeon that operated on stab wounds.

Each party expressed their grievances, and at the end of the meeting, gang members were handed offers of support to combat addiction and seek employment, education, or training.

Failing to accept this offer, the police committed to tackling the violence through arresting the perpetrators. This Community Initiative to Reduce Violence (CIRV), ultimately saw rates of violent crime in Glasgow fall by half and homicide fall by as much as 90% over the past decade.2

The key to the SVRU’s strategy was to acknowledge that collaborative efforts from the police, local government, health organisations, and other community members are crucial to tackling crime. Following their success in Scotland, similar units were nationally scaled to 18 areas across England and Wales in 2019. They save approximately £4.10 for every £1 of funding allocated.3

Onward’s own recent work Levelling Up Locally underscores how crime is symptomatic of wider socio-economic challenges.4 The places we visited faced multiple disadvantages - including high poverty rates, health, and education deprivation, crumbling public services, and fragmented families. These challenges were mutually reinforcing, producing a complex web of issues that collectively and independently contributed to rising crime.

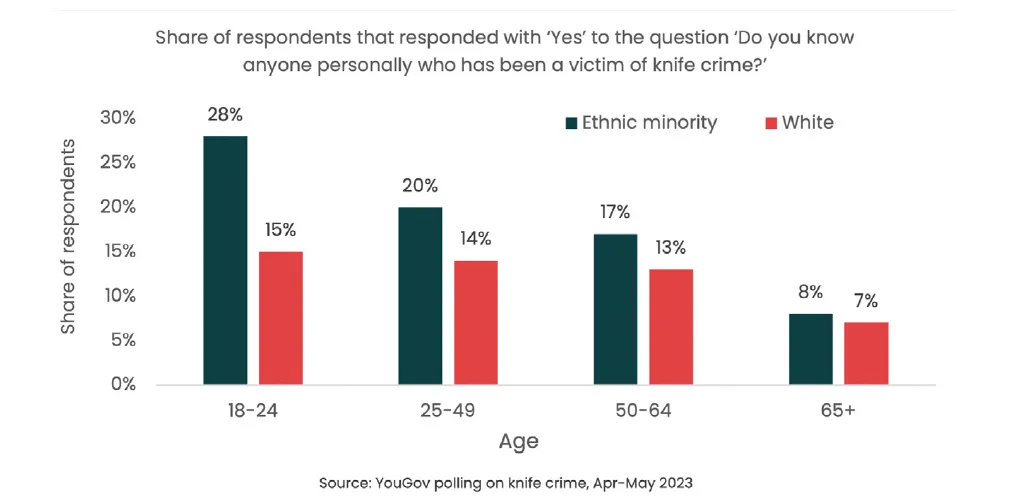

Worryingly, and as the situation in Glasgow highlights, it is young people who are disproportionately contributing to criminal activity. 18-25 year olds make up less than one in ten of the UK population, but were responsible for over a third of all police recorded crime cases in 2019. A major driver of youth violence is exposure: living with a gang member and having a friend in a gang increases the risk of juvenile delinquency. But exposure also means that young people easily fall victim to violent crime. Recent polling on knife crime sees those aged 18-24 affected at much higher rates than other age groups. These differences are particularly stark for ethnic minority communities.

Efforts to tackle violent crime must make greater use of community-oriented solutions that address root causes of violent crime: poverty, family breakdown, and deprivation. Ultimately, this provides the strongest protection against a life of crime. But to be effective, these must be deployed alongside more formal control methods where appropriate, and target both the individual and their immediate surroundings.

There are a number of relatively low-cost and scalable community-based services that target violent crime, particularly among young people.

Starting at the very beginning, early years nurture plays a key role in ensuring that young children develop the right psychosocial skills. But children that undergo ‘adverse childhood experiences’ (ACEs) - such as parental violence, substance abuse, and incarceration - are at much higher risk of being associated with youth violence. And for those with multiple adverse experiences, this risk is even greater.5 A study conducted in Seattle found that a child exposed to seven or more ACEs was 13 times more likely to be recruited into a gang, compared to a child exposed to only a single risk factor.6 Addressing this requires policies to target not just the individual, but the family unit.

A London South Bank University project that asked young people about their experiences joining gangs highlights the importance of families:

“I've got some friends who are gang members, and they have no one at home supporting or helping them with anything…money, schoolwork, general life support – their parents just don't give it to them for some reason.” - Young person, Aged under 18, from Tower Hamlets.7

Families provide the first line of support for anyone vulnerable. But some families need additional help in serving this foundational role. ‘Family Hubs’ provide a package of support services to disadvantaged families - including health, education, and early years support. Local authorities must prioritise accelerating their rollout. But even within existing Hubs, better targeting is needed. Aligning each child’s pupil identification numbers with hub records can help trace an individual’s support requirements across a range of services and ensure that no one is left behind.

Further in a child’s life, schools play an important role in shaping personal and cognitive skills. Experiences at school, both educational and otherwise, mould key behaviours. The pivotal role teachers play in tackling violent crime is well understood by the public. When polled what policies they would support to tackle knife crime, educational programmes in schools garnered the most support - between 73-88%, higher than policies that targeted imprisonment, increased policing, and weapon surrenders.8

After-school activities such as sports clubs have a proven track record in productively diverting young people away from criminal activity. In Oldham, social entrepreneur Moinul Islam runs an afterschool sports club ‘Outta Skool’ that offers classes in boxing, football, and the South Asian sport ‘kabbadi’ to local youths. In inner-city areas, well-designed ‘Multi Use Game Areas’ give young people a safe space to participate in different sporting activities. The Hackney Wick Through Young Eyes report spoke to young people about these areas and the majority reported it was their favourite part of the neighbourhood.9

The public realm has a major role to play in tackling crime. Dilapidated town centres and high streets are commonplace in the country’s neglected neighbourhoods and serve as a breeding ground for criminal activity. But local authorities possess the levers to ensure that public spaces serve the greater good. Legal powers such as Section 215 Notices and High Street Rental Auctions must be deployed more extensively and effectively. Smaller plots of derelict land can be repurposed into ‘Meanwhile Use’ spaces - temporary installations that benefit the community, including art displays, community gardens, and leisure spaces.

But poorly designed public spaces can foster instead of prevent crime. Parks with limited visibility, poor street lighting, and the lack of long-term maintenance plans act as major crime-enablers. An inspiring initiative by the London School of Economics (LSE) and Brent Council demonstrates how public spaces can be made safer and more inclusive for young people. The ‘Samovar Space’ was designed by young LSE Cities apprentices aged 16-24 from the borough. These were young people that were ‘too old for playgrounds but too young for restaurants and bars,’ that applied what they learnt from the programme to create usable spaces.10

But efforts to trace youth violence must transcend the physical realm. While the core focus of street gangs was previously about territoriality, today they are about financial motives.11 Violent crime has become more closely associated with drug and weapons offences, and gang recruitment and negotiations have shifted from the street corner to social media. Scotland Yard’s ‘Social Media Squad’ that monitors gang activity online is a step in the right direction. They forecast future violence and intervene to de-escalate gang violence.12 But greater safeguards are still needed to protect minors against the perils of violence on media platforms.

These community interventions hold great promise, yet the detail lies in delivery. The Glasgow mission was successful because residents trusted their local institutions to deliver on their support. But trust in Britain’s public institutions, including the police, are at an all-time low. By working alongside public authorities, communities can rebuild trust through efficient service delivery. Ultimately, it is only communities that hold the key to tackling violent crime.

Adam Hawksbee

Onward

Shivani H Menon

Onward

Further Reading

[1] Henley, J, ‘Karyn McCluskey: the woman who took on Glasgow's gangs,’ The Guardian, December 19th, 2011

[2] ‘Community Initiative to Reduce Violence, Year 1 Report,’ 2019, Scottish Violence Reduction Unit

[3] ‘Violence Reduction Units, year ending March 2022 evaluation report,’ Home Office research and analysis

[4] Hawksbee, A., Menon, S. H. (2023), ‘Levelling Up Locally,’ Onward report

[5] Gray, P., Smithson, H., Jump, D. (2021). ‘Serious youth violence and its relationship with adverse childhood experiences,’ Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation, Academic Insights 2021/13.

[6] Hill, K. G., Howell, J. C., Hawkins, J. D., & Battin-Pearson, S. R. (1999). Childhood risk factors for adolescent gang membership: Results from the Seattle Social Development Project. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 36(3), 300–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427899036003003

[7] Annan, L.G, Gaoua, N., Mileva K., Borges, M, (2022). ‘What makes young people get involved with street gangs in London? A study of the perceived risk factors.’ Journal of Community Psychology, Volume 50, Issue 5, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22767

[8] Mann, B., ‘How do white and ethnic minority views and experiences of knife crime differ?’ YouGov polling, May 30th, 2023

[9] ‘Hackney Wick Through Young Eyes,’ Hackney CVS, Fairer Hackney, 2018

[10] ‘Apprenticeship programme in City Design: A novel outreach programme for young adults from the London Borough of Brent based at the London School of Economics and Political Science.’ LSE Blog Article

[11] Whittaker, AJ, Cheston, L, Tyrell, T, Higgins,

MM, Felix-Baptiste, C and Harvard, T (2018). From Postcodes to Profits: How gangs have changed in Waltham Forest. London London South Bank University. https://doi.org/10.18744/PUB.002234

[12] Whittaker A, Densely J, Moser, K., S (2020), ‘No two gangs are alike: The digital divide in street gangs’ differential adaptations to social media.’ Computers in Human Behaviour, Volume 110, 106403, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106403